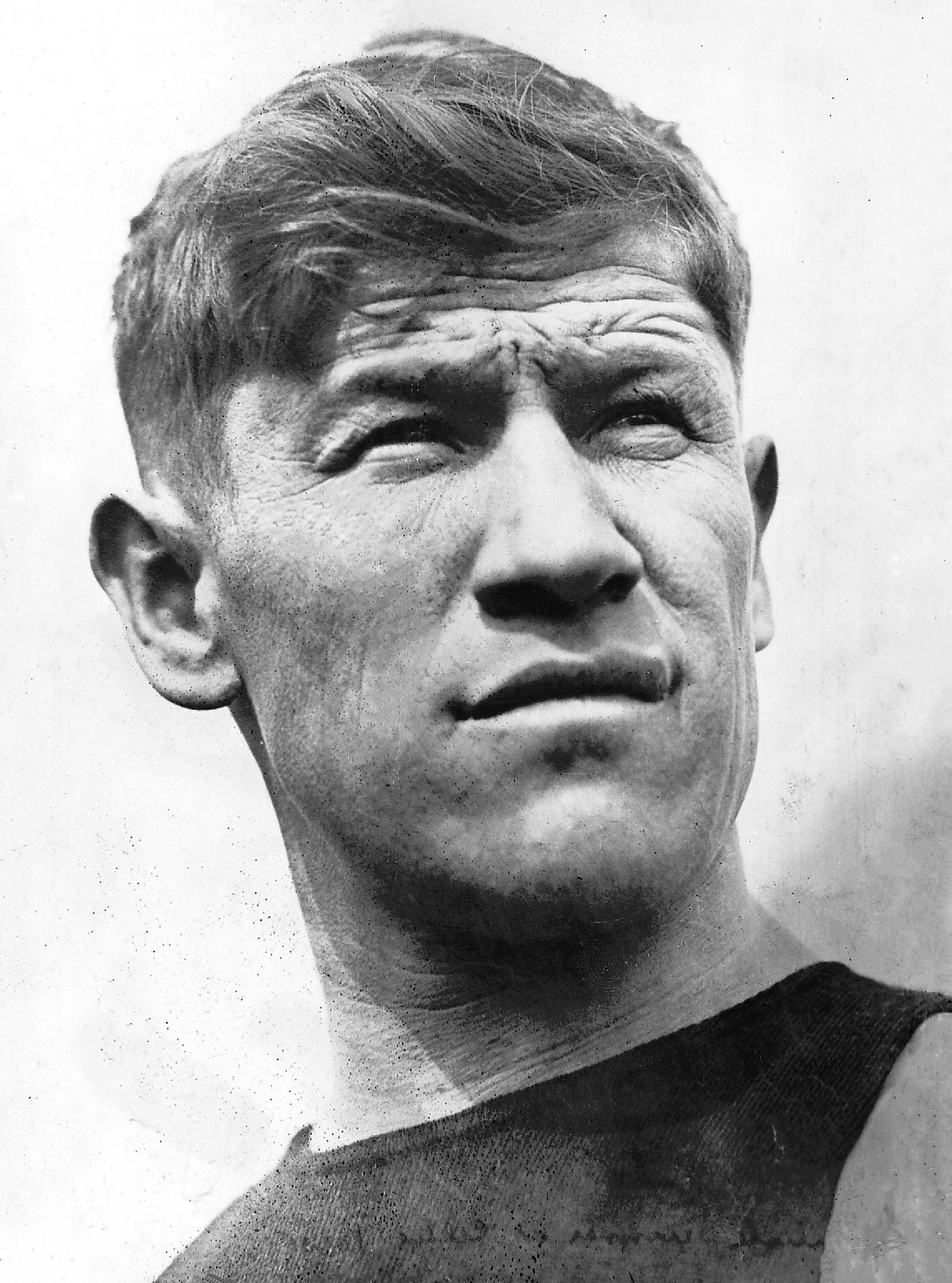

Jim Thorpe, More Than an Unrecognised Champion

I had a friend, once. We went to primary school together, and then high school, before she left, one year earlier than me, to pursue her future, again, one year earlier than me. She wasn't my best friend, and neither was I hers, but I always felt a strong bond with her. Our conversations never got old, and to this day, I regret not spending more time with her. She was, and would still be, one of the few people in my life whose integrity and intentions I would never have to question, whom I could spend an infinite amount of time with and never get to a point where I had to crawl into a boxed room, where I felt my inferiority complex create an invisible contest between myself and the other because they had more of whatever than me. (This was an unfortunate product of my social status, a mirage that often failed to conceal my family's unshakable position at the top of the totem pole that hung from the peak of the little hill guarded by little kings.) She was, simply, one of my few, true equals.

She was also a talented gymnast. This was evidenced by the fact that she decided to leave her home and friends for more competitive pastures. Her goal to be the best was obvious, and, getting to the topic at hand, so was the presumptive desire to make the Olympics, one day.

Now, I have a tough relationship with this event. I feel it is a sham, with no connection to the original games from which it stole its name. It has only ever succeeded in breeding hostility between nations (or, at least, the inhabitants of these nations), as well as leaving cities to writhe in their deflating economic bubbles in its wake. And its corrupt leadership leaves much to be desired. When I observe the obscene popularity of the Olympics, I'm, frankly, rather mystified.

But then, I think about this old friend, who is still on my mind some years later, who I hope managed to reach their goals, and my distaste lessens. It's not our place to spit on the dreams of others, no matter the darkness of the walls within which they occur. Which is why, regardless of my personal feelings, I can still imagine how gut-wrenched Jim Thorpe must have felt after being told that his performance in the 1912 Olympic Games, the greatest ever, was henceforth to be forgotten by the historical record, because he was a no-good cheater.

I have to confess that I was not very familiar with the life of Thorpe, fascinating as it was, until reading Smithsonian magazine's excellent piece on his legendary performance in the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm, and the subsequent fallout upon the discovery that he had "violated the rules of amateurism by playing minor-league baseball in 1909-10." (Of note, in disqualifying him, the International Olympic Committee violated its own rules because no objections to his participation were raised within thirty days of the Games.)

Distrustful of celebrity and fame, Thorpe was a dedicated athlete, having once said, “I may have had an aversion for work, but I also had an aversion for getting beat,” and his motive during the Stockholm Games was not to win, but prove to his future family-in-law that he could support a wife as an athlete. Growing up, his school was a dominant force on the sports field, because their star athlete "won renown football, baseball, track, and lacrosse, and also competed in hockey, handball, tennis, boxing, and ballroom dancing." At one point, Thorpe even single-handedly won a dual against another school, when he took first in the high hurdles, low hurdles, high jump, long jump, shot put, and discus throw. After his performance in the Olympics, in which he competed in 15 events (the pentathlon and decathlon), came first in four of them, and placed in the top-ten in two others, Thorpe went on to play major-league baseball and professional basketball, co-found the National Football League, and move to Hollywood to become a stuntman and actor, before dying of heart failure in 1953 in his "modest but comfortable trailer home."

Thorpe was a remarkable human being, devoted to his passions, wary of the fickle public eye, and, arguably, a physical specimen whose mark on athletics may forever go unmatched. Long after his death, the IOC sent a pair of replica gold medals to his family, but refused to acknowledge him as the undisputed Olympic Champion he was, or recognise the records he broke and continues to hold. It was a token gesture, devoid of meaning, but were he alive, Thorpe wouldn't have cared. He never argued about his disqualification, and never campaigned for his cause. He knew what mattered: "I won 'em, and I know I won 'em."

In the end, I can reconcile my conflicting relationship with the Olympic Games with the fact that, as a whole, they do not matter. Were they to disappear in a puff of white smoke, the world would not change. Life would go on, and the best athletes in the world would still find other ways to compete against each other (such the already-existent World Championships). The only marks the Games leave on society are that they are a mere vessel through which athletes achieve their life-long goals, cities achieve momentary peaks in tourism, businesses see record profits that they'll never see again, and television networks waste exorbitant amounts of money. These are fleeting things. Once the glow wears off, the world stops caring. And the things we're left to remember are not the medals that were won, but the lives of the people who won them, and those who came close.

Thorpe had his medals taken away from him, but he was given what he truly wanted: permission to marry his sweetheart. Despite his tragedy, he still reached his goals.